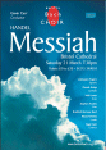

Gavin Carr Conductor

Lesley-Jane Rogers Soprano

Pamela Rudge Contralto

Will Unwin Tenor

Stephen Foulkes Bass

Nigel Nash Organ continuo

Bradford Baroque Band

"... This was a very fresh interpretation which had moments of drama from the

singers, especially in the Hallelujah Chorus. This well-disciplined choir made light work

of His Yoke Is Easy and the haunting Since By Man Came Death whilst Gavin Carr's

intelligent direction helped this to be a successful occasion..."

(John Packwood, Bristol Evening Post)

read more...

In the summer of 1741 Handel, broke and depressed but at the very height

of his musical powers, began setting the text to a new oratorio intended for theatrical use, by his

friend and supporter Charles Jennens: Messiah. Tradition has it that he was a guest that August at

Gopsall Park, the estate of Jennens' grandfather in rural Leicestershire, and here he is said to have

secluded himself for three intense weeks writing Messiah in the Garden Temple, an attractive classical

folly overlooking park, lake and house, whose ruins are still to be seen.

It seems clear that Handel had decided to forsake Italian opera by this time,

having experienced a deal of trouble with his last of that genre, Deidamia, whose scant three performances

in the first two months of the year probably reflect a Handel boycott amongst the opera-mad Quality. It

must have been clear to the composer from the start that he had in his hands a remarkable and unusual libretto

from Jennens, dealing not with a clear narrative such as he had set in Saul and Israel in Egypt just a couple

of years earlier, but instead being a treatment of the origins and spread of Christianity, and a justification

of the doctrine that Jesus Christ was truly the Messiah promised by the Hebrew Prophets. In telling of Jesus'

mission through a selection of those Old Testament texts that were held to predict it, Jennens subtly realised

this didactic aim. Apart from the brief rendition of the Christmas Story (There were shepherds abiding in the

fields), there is neither direct narrative nor overt dramatization to be found in Messiah. Instead, it is the

symbolic and the redemptive that is contemplated and exalted. Placed between the grandly narrative Saul (1738)

on the one hand and the soon-to-be-born Samson on the other, we can grasp how unusual and indeed original Messiah

must have seemed to the composer.

It was Jennen's intention for Handel to perform the oratorio in London in Passion Week,

when staged entertainments were closed and the season was appropriate to the subject, but as events turned out

it proved too useful for his prolonged stay in Dublin, November 1741to June 1742, and Messiah received its

première at Neale's Rooms on the 13th April 1742, after a public rehearsal on the 9th. Controversy surrounded

its premiere as the aged Jonathan Swift, Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral and by then a cranky old man with

Gulliver's Travels long behind him, threatened to withhold his singers from the performance unless Handel

dedicated the proceedings to the benefit of local charities. The issue was, of course, the performance of sacred

texts in a profane place of entertainment, and this was to become a far greater problem in the over-heated cauldron

of the London scene in March of 1743, when Messiah received its London premiere at the Covent Garden Theatre.

Indeed, such was the ruckus over this performance that Handel fought shy of reviving Messiah for the rest of the

decade, and it was only with the performances in the Foundling Hospital Chapel in the 1750s that the work began to

overcome this prejudice and began its exponential trajectory to its status as one of the pillars of Western art..

Messiah is more a contemplation upon things than a telling of stories, as has been said. The scheme of Part I, drawn largely from Isaiah with some quotations from the Gospels, confirms and justifies Jesus Christ's life and mission through a compendium of quotations from the Old Testament dealing in prophecies of the coming of the Saviour of Mankind:

| i - | the prophecy of Salvation: "Comfort ye" and "Ev'ry valley" |

| ii - | the prophecy of the coming of the Messiah: "Thus saith the Lord" |

| iii - | the portent to the world of his coming: "But who may abide?" and "And he shall purify" |

| iv - | the prophecy of the virgin birth and the redemption it will bring: "Behold, a virgin shall conceive", "The people that walked in darkness" and "For unto us a child is born" |

| v - | the appearance of the angels to the shepherds: "There were shepherds abiding in the field" |

| vi - | Christ's redemptive miracles on earth: "Then shall the eyes of the blind be open'd", "He shall feed his flock", and "His yoke is easy" |

Part II opens with a quote from John, draws heavily upon the Psalms, and concludes with a

text from Revelation: the celebrated Hallelujah chorus. Its scheme continues the meditation on themes of sacrifice,

and introduces the idea of evangelism and its spread throughout the world:

| i - | the redemptive sacrifice of Christ's agony: "Behold the Lamb of God" and "He was despised" |

| ii - | his sacrificial death, his passage through hell, and resurrection: "He was cut off" and "But thoudidst not leave his soul in hell" |

| iii - | his Ascension: "Lift up your heads" |

| iv - | God discloses his identity in heaven: "Unto which of the angels" and "Let all the angels of God worship him" |

| v - | Whitsun, the gift of tongues, the beginning of evangelism: "The Lord gave the word", "How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace" and "Their sound is gone out into all lands" |

| vi - | the world and its rulers reject the Gospel: "Why do the nations so furiously rage together?" |

| vii - | God's triumph: "He that dwelleth in Heav'n shall laugh them to scorn", "Thou shalt break them" and "Hallelujah" |

Part III opens with a quotation from Job, and comprises mainly material from First

Corinthians. It ends, as does Part II, with a quotation from the Book of Revelation ("Worthy is the Lamb").

After the dark depths of the second part, it discloses the emergence of grace and the escape from the mortal

round of sin and death that is the fulfilment of prophecy through the saviour's sacrifice:

| i - | the redemption from Adam's fall into sin: "Since by man came death" |

| ii - | the Day of Judgement: "Behold, I tell you a mystery" and "The trumpet shall sound" |

| iii - | the glorification of the Messianic victim: "Worthy is the Lamb that was slain" |

As a performer, it is all too easy to lose sight of the explicitly didactic

aims of Jennens' libretto in the grand succession of immortal masterpieces that Handel wrote to clothe it.

From a spiritual perspective, too, it may possibly be hard to engage with the libretto unless you are a

Christian of somewhat fundamental bent. But the strength of Handel's response to the text carries all

before it. His operatic mastery of form through careful but seemingly effortless juxtapositions of repose

and energy, and his unequalled ability to pile up the tension in blocks of choral textures both small and

large propels the listener and the performer alike inexorably through the mounting tensions of Jennens'

conception into the unrivalled brilliance of the final chorus and the greatest of all Amens.

After twenty-five years of singing and conducting Messiah more than thirty times, it may be thought strange that tonight's conductor should admit to not having previously assessed the true intent of Jennens' work. But he humbly offers this admission as proof positive of two things: the overpowering glory of Handel's response in music; and the musician's own over-powering weakness in the face of great music! For it is surely true for all musicians when faced with Messiah, that the music is enough and that Handel's interpretation of scripture is enough, that the words do not in fact exist for the meanings that Handel reveals in Jennen's libretto, great and original though it is, and that this is why you have chosen to spend this evening in a cathedral with hundreds of others, instead of at home, wrapped up warm, with a Book.

© Gavin Carr 2009

BRADFORD BAROQUE BAND was formed in 1996 to perform chamber music on period instruments. The repertoire ranges from Baroque sonatas, arias and concertos to Schubert songs. Based in Bradford-on-Avon, the band frequently expands to accompany choral works such as the Monteverdi Vespers and Bach's Mass in B minor.

| Violins: | Alison Townley (leader), Ann Monnington, Cath Black, Peter Fender, Liz Hodson, Karen Raby, Rachel Gough, Philippa Lodge |

| Violas: | Liz Fowler, Kate Thomas, Rachel Thornton |

| Cellos: | Mark Davies, Keith Tempest |

| Double bass: | Gaynor James |

| Trumpets: | Simon Munday, Andy Webb |

| Oboes: | Belinda Paul, Jane Downer |

| Bassoon: | Mike Brain |

| Timpani: | Scott Bywater |